Article

EMA to Review Olaparib in BRCA-mutated, HER2-negative Breast Cancer

Author(s):

The European Medicines Agency has accepted a marketing authorization application for olaparib to treat women with BRCA-mutated, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer who previously received chemotherapy in the neoadjuvant, adjuvant, or metastatic setting.

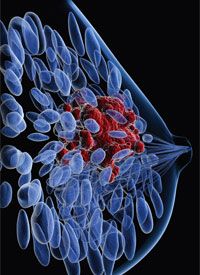

breast cancer

The European Medicines Agency has accepted a marketing authorization application for olaparib (Lynparza) to treat women with BRCA-mutated, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer who previously received chemotherapy in the neoadjuvant, adjuvant, or metastatic setting.

The submission is based on results from the phase III OlympiAD trial, which showed that the PARP inhibitor olaparib reduced the risk of disease progression or death by 42% and improved progression-free survival (PFS) by 2.8 months versus standard chemotherapy in previously treated patients with BRCA-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer.

OlympiAD included 302 patients with HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer who harbored germline BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Patients were recruited in 19 countries across Europe, Asia, North America, and South America, and received up to 2 prior lines of chemotherapy in the metastatic setting.

The median patient age was approximately 45 and about one-third of patients were non-white (mainly Asian). There was a nearly even number of patients in both arms who were hormone-receptor positive and triple negative.

Across the overall study population, 71% had received prior chemotherapy in the metastatic setting, and 28% had received prior platinum-based therapy in the neoadjuvant, adjuvant, or metastatic setting. Patients who received prior platinum regimens had to have completed the therapy within 12 months of starting the trial.

Patients were randomly assigned to 21-day cycles of 300 mg twice daily oral olaparib (n = 205) or physician’s choice of standard chemotherapy (n= 97; capecitabine, vinorelbine, or eribulin). The primary endpoint of the trial was PFS per a blinded independent review.

The PFS analysis occurred after 163 events in the olaparib cohort and 71 events in the chemotherapy group. The median PFS was 7.0 months in the olaparib arm versus 4.2 months with standard chemotherapy (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.43-0.80; P = .001).

At 12 months, 25.9% of the patients in the olaparib group and 15.0% of the patients in the standard-therapy group were free from progression or death. Overall, 52% of patients had a second progression event or had died after a first progression event. The median time from randomization to a second progression event or death after a first progression event was 13.2 months in the olaparib group and 9.3 months in the standard-therapy group (HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.40-0.83; P = .003).

Ninety-four patients (45.9%) in the olaparib group and 46 patients (47.4%) in the standard-therapy group died by the time of the primary analysis. Median time to death was 19.3 months in the olaparib group and 19.6 months in the standard-therapy group. Overall survival (OS) was similar between the two groups (HR for death, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.63-1.29; P = .57).

According to blinded independent central review, 100 of the 167 patients who had measurable disease responded to treatment. The response rate was 59.9% (95% CI, 52.0-67.4) in the olaparib arm compared with 28.8% (95% CI, 18.3-41.3) in the standard-therapy group. Investigators observed complete response (CR) in 9.0% of the patients who had measurable disease in the olaparib group and in 1.5% in the standard-therapy group.

The median duration of response was 6.4 months in the olaparib group and 7.1 months in the standard-therapy group. The median time to the onset of response was 47 days and 45 days, respectively.

Olaparib was well tolerated overall, with fewer than 2.0% of patients discontinuing treatment due to toxicity, compared with 2.2% in the chemotherapy arm. The main adverse events (AEs) associated with the PARP inhibitor were nausea, anemia, and fatigue.

Notably, in the olaparib arm versus the chemotherapy arm, there were fewer grade ≥3 AEs (36.6% vs 50.5%, respectively) and fewer AE-related discontinuations (4.9% vs 7.7%). The PARP inhibitor also had less of a negative impact on white blood cells compared with chemotherapy.

There was 1 death in each treatment group, a case of sepsis in the olaparib group and a case of dyspnea in the standard-therapy group. No cases of myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myeloid leukemia were noted in either treatment group.

Merck (MSD) noted in a press release that this is the first time an approval has been sought in Europe for a PARP inhibitor in breast cancer. The company entered an agreement with AstraZeneca in July 2017 to jointly develop olaparib. The US FDA approved olaparib in this setting based on the same data in January of this year.

Robson M, Im SA, Senkus E, et al. Olaparib for metastatic breast cancer in patients with a germline BRCA mutation. 2017;377:523-33. N Engl J Med. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1706450.

%20(2)%201-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered.jpg?fit=crop&auto=format)

%20(2)%201-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered-Recovered.jpg?fit=crop&auto=format)