Dual HER2-Targeted Approaches in Breast Cancer

Episodes in this series

Mark Pegram, MD: Dr O’Shaughnessy, Dr Chau Dang set the stage for this discussion by introducing the concept of dual HER2 [human epidermal growth factor receptor 2]–targeted antibody therapies, both in the first-line metastatic setting in the case of the CLEOPATRA trial but also in the adjuvant setting for early stage for HER2-positive breast cancer in the case of the APHINITY trial.

Can you drill down on those 2 studies in just a little more detail? Talk about the long-term follow-up from the CLEOPATRA study, for example, and talk a little about the safety data from this dual-antibody approach and how these have changed practice in terms of the landscape of therapy for both early and late-stage breast cancer.

Joyce O’Shaughnessy, MD: Sure, I’d be happy to. That was a great summary there, Chau—a really lovely, complete summary. The dual targeting with trastuzumab and pertuzumab, both of those antibodies were aimed at HER2. HER2 can certainly be amplified and often is. It can heterodimerize but also homodimerize, but it can also heterodimerize and can be ligand-driven with heregulin, which binds to HER3 and then complexes with HER2. The trastuzumab-pertuzumab combination with them binding to different domains of HER2 with pertuzumab binding at the heterodimerization domain of HER2, it stops not only homodimerization but also heterodimerization, which is very important in HER2 biology.

It made a great deal of sense to take this forward into the metastatic setting, as Chau said. In the CLEOPATRA trial, patients with first-line HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer were randomized to docetaxel and trastuzumab with placebo vs. docetaxel, trastuzumab plus pertuzumab, and first-line metastatic. The results, as Chau said, were very striking in terms of very important improvement in progression-free survival but also a 15.7-month improvement long-term in overall survival. I don’t think we’ve really seen that kind of a survival delta really any time in HER2-positive breast cancer, likely in any of our metastatic breast cancer settings. This was an amazingly large improvement in overall survival.

That really set the stage of course to bring this combination into the high-risk curative setting, as Chau said. Initially, in the preoperative setting with NeoSphere and TRYPHAENA, which led to pathologic complete response rates that were in the 45% range with ER-positive disease, they were in the 80% range when you gave the anthracycline preoperatively along with taxane, trastuzumab, and pertuzumab. There were very big improvements in pathologic complete rates. That led to the conditional accelerated approval of the combination preoperatively until the data from APHINITY were available, where the physicians had a choice of a taxane, carboplatin, trastuzumab plus-or-minus pertuzumab regimen, or an anthracycline regimen followed by taxane-trastuzumab with or without pertuzumab. There were a couple of different chemotherapies. About half of patients received anthracycline and half received nonanthracycline chemotherapy.

The trial was largely node-positive patients. There were a proportion of patients that were node negative, but then they closed that cohort down to enroll a much higher-risk population. We had recent data of a 6-year update, the mature data from APHINITY. Patients received either the trastuzumab chemotherapy with placebo or trastuzumab-pertuzumab with chemotherapy. The chemotherapy—when that was stopped, they finished then the year of the trastuzumab placebo or trastuzumab-pertuzumab. A year of therapy.

When you look at the intent-to-treat population at the 6-year follow-up, it was a 2.8% improvement in disease-free survival that was statistically significant. Interestingly, pretty much all the benefit was in the node-positive population. There was a 4.5% improvement in disease-free survival, which is certainly a clinically meaningful 4.5%. The toxicity, thankfully, with the addition of the pertuzumab both in the metastatic setting and in the curative setting, is highly manageable.

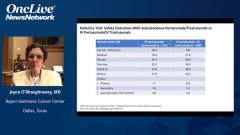

The main thing is diarrhea when the pertuzumab-trastuzumab is combined with chemotherapy. Once the patient stopped the chemotherapy, whether in the metastatic or neoadjuvant setting, then the diarrhea basically largely abates with the pertuzumab. It’s actually very manageable. I must say, these days of course, in practices for the higher-risk patients, we’re treating them preoperatively with chemotherapy, pertuzumab, and trastuzumab. If they have a pathologic complete response and they were high-risk to start off, we continue the pertuzumab and trastuzumab to finish the year. If they still have residual disease, they get the T-DM1 [trastuzumab emtansine] for the KATHERINE trial, as Chau told us.

Diarrhea is definitely an issue in some grade 3 diarrhea that can be running in 20% or more. Certainly with the proactive use of loperamide, what I do is 2 loperamide after the first loose stole of each day, and then 1 loperamide after each subsequent loose stool that day. Within a couple or 3 doses, it shuts down. Once the patients get a few days beyond that, usually the diarrhea abates. Then it usually goes away once they finish the chemotherapy, and they’re finishing their year of pertuzumab and trastuzumab if they had a pathologic complete response.

There was no additional cardiac toxicity in the CLEOPATA trial with the addition of the pertuzumab. There was a very small increment in cardiac toxicity in the APHINITY trial, with the addition of pertuzumab. Other than that, you can get some rash with pertuzumab, but it’s not usually very substantial. It’s mainly diarrhea, which we’re all very used to using it at this point. It’s basically to just take a proactive approach with antidiarrheal medicine.

Transcript Edited for Clarity